A special workshop at the Royal Library (KBR) in Brussels

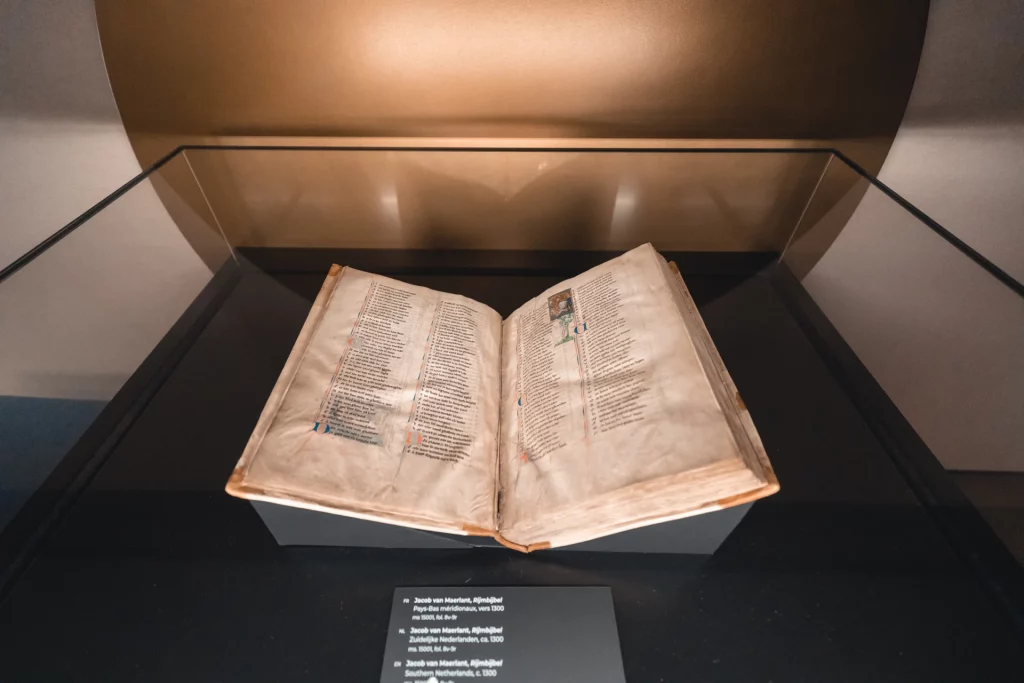

On Saturday 27 May 2023, I had the privilege of leading a workshop at the studio of the Museum of the KBR, (Royal Library) in Brussels. The workshop took place around an exhibition on Jacob van Maerlant’s Rhyme Bible that opened at the KBR in May. Several activities were planned including a miniature painting workshop.

Noah in the ark. Image used during the workshop.

The Rhyme Bible

The Brussels version of the Rhyme Bible is back on display after 10 years. And it is worth it considering that this version is not only the oldest but also the most richly illustrated.

Rhyme Bible in Brussels. Source: KBR.

The Rhyme Bible is a work by Jacob van Maerlant, a 13th-century Flemish poet. He was born around 1230 in the region around Bruges. Besides the Rhyme Bible, Jacob wrote other works such as: Alexanders geesten (On the exploits of Alexander the Great 1255), Den Naturen Bloeme (1268), and the Spiegel Historiaal (1288). The Rhyme Bible was finished in 1271.

The name Rhyme Bible is not quite correct because it is not a fully rhymed Biblical text. The Rhyme Bible is an adaptation of the: Historia scholastica by Pierre le Mangeur also known as Petrus Comestor. That work was a leading manual for learning biblical history. It was used at the theological faculty in Paris, among other places.

Furthermore, in addition to the text of the Bible, the Rhyme Bible contains another work called ‘the Wrath’. That text is based on work by the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, in which he recounts the siege, capture and destruction of Jerusalem.

What is special about the Rhyme Bible from Brussels is that the work was probably created during Jacob van Maerlant’s lifetime, namely in the late 13th century. Jacob himself called his translation ‘Scholastica in dietshen’ or also Historia scholastica in the Dietsche vernacular. The name: ‘Rhyme Bible’ dates from the late Middle Ages and is probably meant to distinguish Jacob’s rhymed adaptation from the History Bible written in prose.

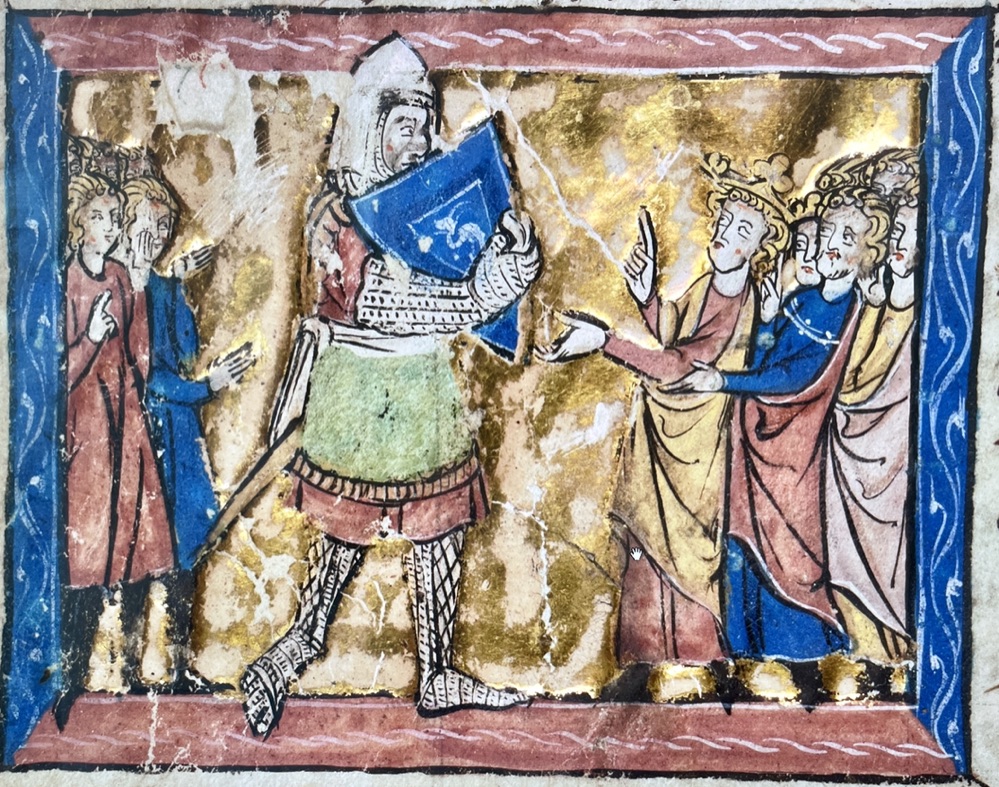

David and Goliath. Fig used during the workshop.

No other work by Jacob van Maerlant has survived so many manuscripts. Maerlant’s Rhyme Bible was a popular work that was copied for two centuries. It is not known how many Rhyme Bibles were ever produced, but today 64 text witnesses of the Rhyme Bible still exist. A very high number for a text dating back to the 13th century. Executed both on parchment and paper, some soberly others beautifully illuminated. The two copies that stand out are the Bibles in Brussels and The Hague. The former kept in the Royal Library and the latter in the Museum of the Book. The Brussels Bible is somewhat older and contains 159 small miniatures and four margin decorations. The Rhyme Bible from The Hague contains 72 miniatures, one of which is full-page.

The Rhyme Bible fitted a growing demand for illustrated Bible texts for an affluent audience in the late 13th century. Books were commissioned for this clientele in the urban environment of the time. In the cities, it was specialised craftsmen who were responsible for the production of books. Arrangements were made in advance about raw materials to be used, working hours, division of labour, etc. There were also a kind of ‘book brokers’ , who had to take care of everything. In the 15th century, such a coordinator was called: ‘librarian’.

Six specialists were involved in the production of the Rhyme Bible: the parchment maker, the copyist, the florist, the gilder, the miniaturist and the bookbinder. The “flourisher” took care of the red and blue letters and the filigree work (=pen work).

The siege of Jerusalem. Image used during the workshop

The support for the text in the Rhyme Bible is medium-quality calf parchment. Its thickness is 0.2 mm. Bible manuscripts of the 12th and 13th centuries were often written on calf parchment, the best quality. Other works such as those for rhetoric and grammar were mostly written on sheep parchment which was much (3x) cheaper.

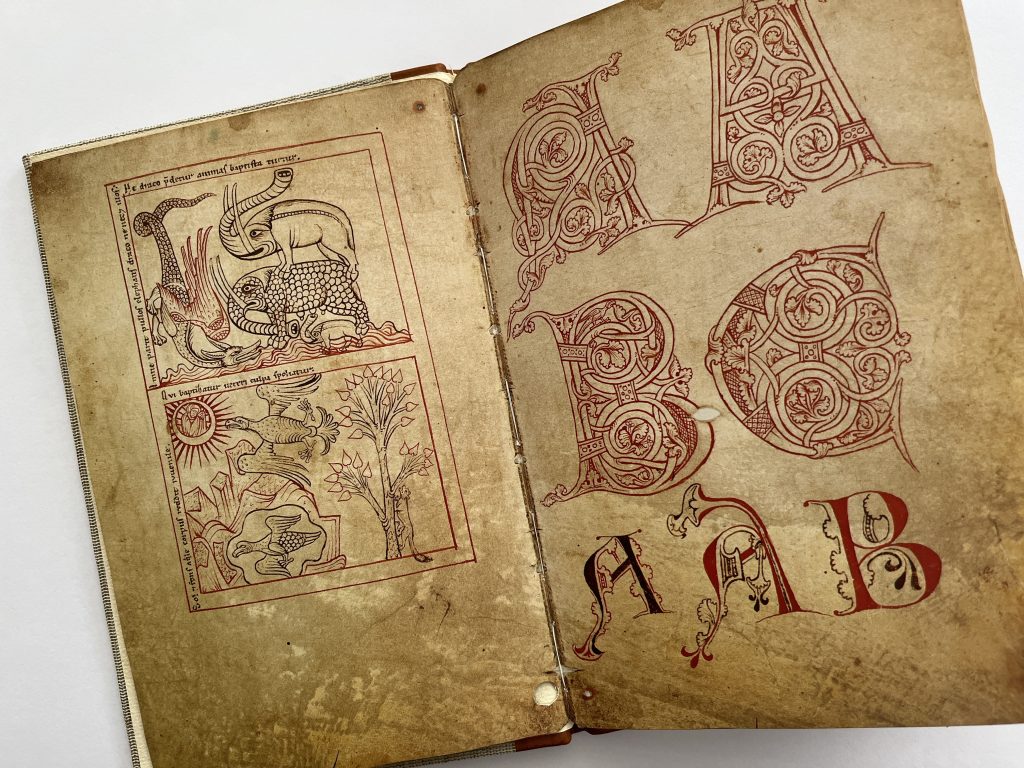

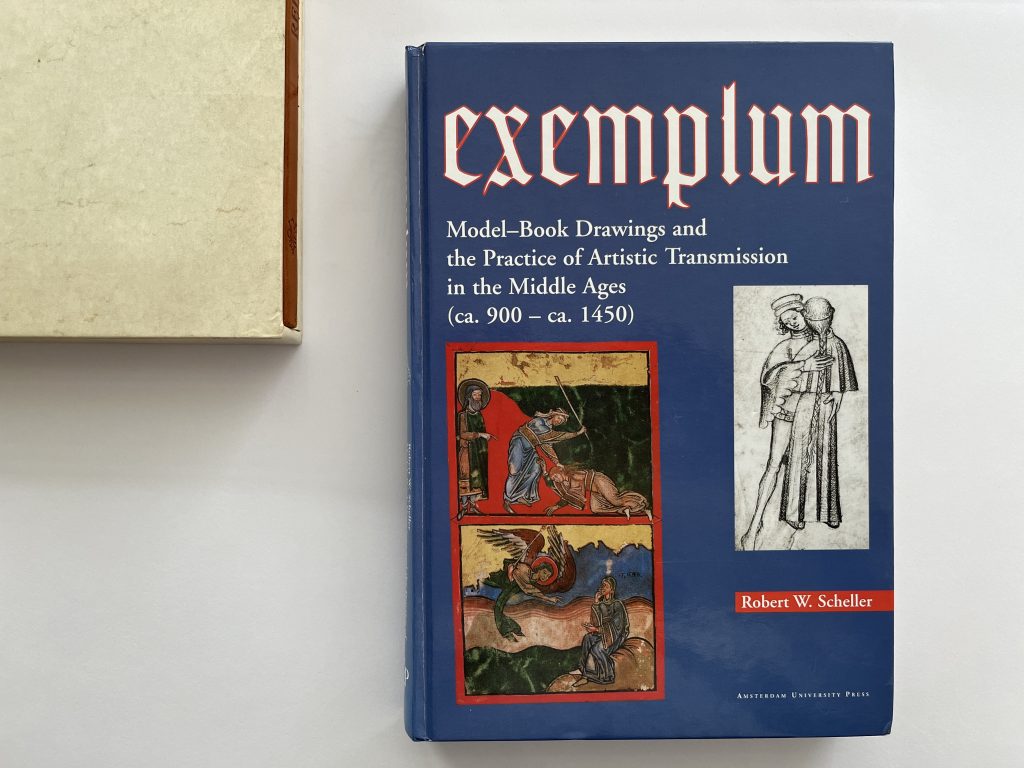

Stylistically, the miniatures are strongly influenced by the French Gothic style. We can see this in the elongated figures against a background of gold leaf or flat decorations. Miniaturists at the time made ample use of model books (exempla) when creating the miniatures for manuscripts. As far as is known, this was done as early as the 10th century.

Image from a model book: Reiner Musterbuch. Photo Jaap Boerman

Study of the use of model books in the production of manuscript miniatures.

Image from a model book: Reiner Musterbuch. Photo: Jaap Boerman

The colour palette for the miniatures from the Brussels Rhyme Bible is largely similar to the common palette of the period.

Lead white: as white and mixed with azurite for light blue.

Azurite: mixed with lead white and a natural ochre to make a different shade of blue.

Minium: Lead(orange-red).

Red: An unreducible organic red precipitated on a substrate of lime.

Green: Malachite and Verdigris.

Yellow: Operment or Auripigment.

Brown and Beige: Earth colours, yellow-brown ochres.

Black: Soot due to charring.

The binding of the current Bible is from the 18th century. Previously, the Bible had a light parchment binding a so-called: ‘Spitselband’. The first binding was a 13th century binding with wooden boards covered with leather.

Layout of a replica of a 13th century binding with wooden covers. Photo: Karin Cox. Ars Ligandi.

The Rhyme Bible has not been on display for 10 years due to fragility especially that of the gold layers in the miniatures. Earlier in the 19th century, it was restored with the insights of the time. Vanished faces were repainted. Furthermore, colours of the time were used and parchment was restored with thin dyed paper.

Currently, stabilisation is more of an option than restoration. In recent times, people have tackled the flaking gold layer by applying a solution of support glue, also known as Isinglass, to it. Two per cent Isinglass dissolved in demineralised water has been found to be consolidating.

For those who want to know more about the Rhyme Bible, a new book has now come out on the Rhyme Bible.

De Rijmbijbel van Jacob van Maerlant, Het oudste geïllustreerde handschrift in het Nederlands Uitgeverij: Walburgpers.

Door: Jan Pauwels, Bram Caers (red).

The Rijmbijbel has achieved a canonical status for its significance in the development of the Dutch language. At the same time, the illuminations in this manuscript can be considered to be the most important Early Netherlandish paintings. The text of the Rijmbijbel was written by Jacob van Maerlant, he was the most important Netherlandish author of the Middle Ages. He was the first to put the whole Bible in rime in the Netherlandish language.