Model-Book Drawings and the Practice of Artistic Transmission in the Middle Ages

Gebruikten de middeleeuwse verluchters voorbeelden?

EXEMPLUM

Model-Book Drawings and the Practice of Artistic Transmission in the Middle Ages

“During the Middle Ages, artistic ideas were transmitted from one region to another and passed on from one generation to the next, in the form of drawings. This kind of handmade reproduction, ‘exemplum’ in Latin, was used to record the form and content of works of art. Some of those drawings have survived in ‘model books’. The author presents a fascinating account of many and various aspects of these drawings with special emphasis on how they contribute to our understanding of the genesis of medieval works of art. Exemplum will be a standard work of reference for many years to come”.

(Ca. 900-ca. 1450). Robert W. Scheller

Een poosje terug, kocht ik een boek met bovenstaande titel. De reden was dat ik mij meer wilde verdiepen in het gebruik van ‘voorbeelden’ bij het maken van miniaturen in handschriften. Hoe zit dat eigenlijk, gebruikten de middeleeuwse verluchters voorbeelden of ook wel exempla genoemd bij het maken van hun miniaturen? En zo ja, welke rol speelden die eigenlijk bij het tot stand komen van die miniaturen? Deed de verluchter alles uit het hoofd of werden er juist modellen gebruikt? Bestonden er schetsboeken in de zin zoals wij die kennen? Kortom een heleboel vragen die je kunt stellen rondom het maken van miniaturen in middeleeuwse handschriften.

A while ago, I bought a book with the above title. The reason was that I wanted to learn more about the use of ‘examples’ when making miniatures in manuscripts. What about that actually, were medieval illuminators using examples or also called exempla when making their miniatures? And if so, what role did they actually play in the creation of those miniatures? Did the illuminator do everything by head or did he use models? Were there sketchbooks in the sense we know them? In short, a lot of questions you can ask about the making of miniatures in medieval manuscripts.

Mijn interesse hiervoor is al in het verleden gewekt door het schetsboek van: Villard de Honnecourt uit de vroege 13e eeuw. Ik heb het ooit eens gedownload via Gallica, een prachtig schetsboek vol mooie tekeningen, met veel details en heel verassend. Bij het bekijken van zijn werk vraag jezelf dan af, waarom heeft hij het gemaakt en hoe en eventueel wie hebben er naast hemzelf gebruik van gemaakt? Toen ik echter een ander werk: -een facsimile uitgave van het: Reiner Musterbuch- op de kop tikte was ik verkocht en wilde ik meer van dit soort werken en hun gebruik weten. Het boek: Exemplum dat ik in de literatuur hierover tegenkwam was dan ook een uitstekende handleiding om mij hier eens verder in te verdiepen.

My interest in this has already been triggered in the past by the sketchbook of: Villard de Honnecourt from the early 13th century. I once downloaded it through Gallica, a wonderful sketchbook full of beautiful drawings, with lots of details and very surprising. When looking at his work, you then wonder, why did he create it and how and possibly who used it besides himself? However, when I saw another work: -a facsimile edition of the: Reiner Musterbuch- I was sold and wanted to know more about these kinds of works and their uses. So the book: Exemplum that I came across in the literature on the subject was an excellent guide to study it further.

Het boek is een heel gedegen wetenschappelijke studie over deze materie en tijdens het lezen maakte ik dan ook volop aantekeningen. Die aantekeningen zijn de rode draad van dit bericht geworden.

Dit bericht is dus geen samenvatting van het boek in strikte zin, maar een verslag van persoonlijk gemaakte aantekeningen. Uiteraard sterk ingekort maar ik hoop toch dat het interessant genoeg is voor de lezer.

The book is a very solid scientific study on the matter, so while reading it, I took plenty of notes. Those notes have become the thread of this post.

So this post is not a summary of the book in the strict sense, but a record of personally made notes. Obviously greatly abridged but I still hope it is interesting enough for the reader.

Introductie:

Tegenwoordig is de waardering voor een tekening zoals wij die kennen heel anders dan vroeger in de Middeleeuwen. Vandaag de dag waarderen wij een tekening als een artistieke expressie van een kunstenaar. Hoe beroemder zo’n kunstenaar is des te meer waardering er is voor zijn tekeningen. Eigenlijk is die waardering van een tekening als artistiek werk er pas vanaf de Renaissance, midden 15e eeuw. Het is daarom dan ook begrijpelijk dat vanaf dat moment meer tekeningen zijn overgeleverd dan voor die tijd. De tekening was toen pas waard om op zich te worden bewaard als een ‘kunstwerk’.

Is dit de reden dat dat er meer tekeningen overgebleven zijn uit de Renaissance dan uit de Middeleeuwen? Of zijn er ook nog andere factoren die een rol hebben gespeeld? In het boek gaat de auteur verder op zoek naar antwoorden.

Today, the appreciation of a drawing as we know it is very different from what it used to be in the Middle Ages. Today, we appreciate a drawing as an artistic expression of an artist. The more famous such an artist is, the more appreciation there is for his drawings. Actually, that appreciation of a drawing as an artistic work has only been there since the Renaissance, mid-15th century. It is therefore comprehensible that more drawings have survived from that time onwards than before. Only then was the drawing worth preserving in its own right as a ‘work of art’.

Is this the reason that more drawings have survived from the Renaissance than from the Middle Ages? Or are there other factors that also played a role? In the book, the author continues to search for answers.

Een aantal uitgangspunten bij het onderzoek naar modelboeken en hun gebruik

- Zoals hierboven al gezegd was de tekening in de Renaissance een artistieke expressie van een kunstenaar zelf. De creatieve kracht van zijn persoonlijkheid of individu werd direct en helder zichtbaar gemaakt. Juist daarom werd de tekening vanaf die tijd steeds meer gewaardeerd.

- In de Middeleeuwen echter was de tekening een voorbereidende fase, een studie van de natuur, een compositie schets, een werktekening. De tekenaar had al werkend een heel divers of juist specifiek doel voor ogen.

- Tekeningen gemaakt met een loodstift, pen penseel waren onderdeel van de stappen die gemaakt moesten worden om een doel te bereiken. Zij waren daar een essentieel onderdeel van. Je zou kunnen zeggen dat ze meer een praktisch nut hadden.

- Ook bij de training van de kunstenaar was het maken van tekeningen heel belangrijk. We kunnen dat lezen bij Cennino Cennini in zijn: ‘Handboek van de Kunstenaar’.

Bron: Pierpont Morgan Library

Some guiding principles in researching model books and their use

As mentioned above, drawing in the Renaissance was an artistic expression of an artist himself. The creative power of his personality or individual was made directly and clearly visible. This is precisely why the drawing was increasingly appreciated from that time onwards.

In the Middle Ages, however, the drawing was a preparatory phase, a study of nature, a composition sketch, a working drawing. While working, the draughtsman had a very diverse or just specific purpose in mind.

Drawings made with a lead pen, brush were part of the steps to be made to achieve a goal. They were an essential part of that. You could say they had more of a practical use.

Drawing was also very important in the training of the artist. We can read that from Cennino Cennini in his: ‘Handbook of the Artist’.

Nog steeds is niet de vraag beantwoord waarom er dan zo weinig is overgebleven van al die tekeningen uit de Middeleeuwen.

Een aantal redenen op een rijtje:

- Tekeningen hadden zoals al gezegd geen artistieke waarde en werden dan ook niet met zorg bewaard. Ze dienden een heel specifiek doel en bij het bereiken daarvan was de tekening niet veel meer waard. Als het project was afgerond kon de tekening worden weggegooid

- Wat voor ons moeilijk is voor te stellen is dat het materiaal om op te tekening op te maken heel schaars en duur was. Wij hebben heel veel keuze voor het kiezen van een drager voor het maken van een tekening. Maar vóór de 15e eeuw en de introductie van het papier was er alleen perkament beschikbaar als duurzame drager om op te tekenen.

- Er werden daarnaast ook wel andere en minder duurzame dragers gebruikt om tekeningen op te maken. Wijd en breid was het gebruik van de wastafel. Die werd gebruikt door handelaren voor o.a. het vastleggen van transacties, maar ook om te oefenen met schrijven en het maken tekeningen. Echter ook hier is bijna alles verloren gegaan.

Still unanswered is the question of why then so little remains of all those drawings from the Middle Ages.

Some of the reasons listed:

Drawings, as already mentioned, had no artistic value and were therefore not kept with care. They served a very specific purpose and upon achieving it, the drawing was not worth much anymore. When the job was finished, the drawing could be discarded

What is hard for us to imagine is that the material to draw on was very scarce and expensive. We have a lot of choices for choosing a support for making a drawing. But before the 15th century and the introduction of paper, only parchment was available as a durable medium to draw on.

Other and less durable supports were also used to make drawings on. Widely used was the sink. These were used by merchants for recording transactions, among other things, but also for practising writing and making drawings. However, here too, almost everything has been lost.

Onderzoek naar modelboeken en hun rol in de kennisoverdracht.

Bij het onderzoek naar de modelboeken is lang de these van Julius von Schlosser gebruikt: Künstliche Überlieferung. De gedachte hierachter is dat de kunstenaar zich niet zo zeer liet leiden door de natuur maar door modellen die waren geworteld in de Oudheid.

Vanaf de Oudheid zouden zich zekere modellen hebben ontwikkeld die meer leidend waren bij de vormgeving van de miniaturen dan de natuur zelf. Anders gezegd: de kunstenaar keek meer naar het model voor zich of gevormd in zijn hoofd dan naar de vorm in de natuur om hem heen. Nu zij zijn wij gewend om te tekenen naar de natuur maar voor een middeleeuwer lag dat anders.

Bron: Pierpont Morgan Library.

Het model of ook wel exemplum is de ene kant, het startpunt op de weg naar het eindproduct, daar begon de kunstenaar. Om de weg te gaan naar het eindproduct maakte hij tekeningen. Wij zouden zeggen: ontwerpen. In die optiek was de tekening de overbrugging tussen het exemplum of het voorbeeld en het eindproduct. Dit is lang een belangrijke gedachte geweest bij alle onderzoek naar de rol van modelboeken

In meer recent onderzoek is deze opvatting wel aan kritiek onderhevig en wordt er genuanceerder over gedacht. In het boek exemplum gaat Scheller hier dieper op in. Echter is dit bericht geen echte studie en heb ik alleen de meest relevante opmerkingen in mijn stukje verwerkt.

Volgens Scheller is ook bij het onderzoek naar de modellenboeken een gedetailleerde semantische studie nodig voor het juiste begrip van het kunstvocabulaire in de Middeleeuwen. Het is nog niet zo eenvoudig om de gebruikte termen in de bronnen die worden gebruikt voor onderzoek te duiden.

Woorden die in bronnen worden gebruikt als: imitare, praesentare, exemplum, exemplar, forma, similitudo, imago moeten in een brede context worden gezien en waarom eigenlijk?

Research on model books and their role in transmission of knowledge.

The research on model books has long used Julius von Schlosser’s thesis: Künstliche Überlieferung. The idea behind this is that the artist was guided not so much by nature but by models which were rooted in Antiquity.

From Antiquity onwards, certain models would have developed that were more leading in the design of miniatures than nature itself. In other words, the artist looked more at the model in front of him or formed in his mind than at the form in nature around him. Now they we are used to drawing after nature but for a medievalist it was different.

The model also called exemplum is one side, the starting point on the way to the final product, that is where the artist started. To make his way to the final product, he made drawings. We would say designs. In this view, the drawing was the bridge between the exemplum or example and the final product. This has long been a key idea in all research on the role of model books

In more recent research, however, this view is subject to criticism and more nuanced thinking. In the book exemplum, Scheller examines on this. However, this post is not a real study and I have only included the most relevant comments in this post.

According to Scheller, a detailed semantic study is also needed for the proper understanding of art vocabulary in the Middle Ages when researching model books. It is still not so easy to make sense of the terms used in the sources used for research.

Words used in sources like: imitare, praesentare, exemplum, exemplar, forma, similitudo, imago need to be seen in a broad context, and why really?

Taal is een iets schitterends, het is één van de prachtige gaven aan de mens gegeven. Maar taal kan ook lastig zijn, het let nauw wat en hoe je het zegt en welke woorden je gebruikt. Je kunt met woorden een ander prijzen maar ook vernederen. Wie bewust leeft gaat bewust met de taal om.

Is dit van belang in het dagelijks leven dan zeker ook in het onderzoek naar bronnen die spreken over modellen en hun gebruik bij miniaturen. Zonder daar al te diep op in te gaan moeten we ons realiseren dat bovengenoemde woorden door de middeleeuwers werden gebruikt, gevormd en geïnterpreteerd.

Daarbij gebruikten zij de filosofie van Plato, Aristoteles en zeker ook de theologie van de kerkvaders en dat maakt het allemaal nogal complex, te veel voor dit bericht. Het boek echter gaat er uiteraard dieper op in en dat is heel boeiend.

BM, lat. 4

Language is a wonderful thing, it is one of the wonderful gifts given to human beings. But language can also be tricky, it pays close attention to what and how you say it and what words you use. You can use words to praise another person but also to humiliate them. Those who live consciously deal with language consciously.

If this is of importance in everyday life, then certainly also in researching sources that talk about models and their use in miniatures. Without going into too much detail, we should realise that the above words were used, shaped and interpreted by medieval people.

In doing so, they used the philosophy of Plato, Aristotle and certainly also the theology of the Church Fathers, which makes it all rather complex, too much for this post. The book, however, obviously delves deeper into it and it is quite fascinating.

De bronnen voor het onderzoek naar modelboeken zijn relatief schaars. Om een compleet beeld te vormen is er ook inbreng nodig via andere ‘kanalen’. Het is daarom belangrijk dat al bestaande kennis over de overdracht van ideeën op artistiek gebied in de Middeleeuwen worden meegenomen zoals:

- De rol van de rondreizende kunstenaar met een collectie modellen in zijn bagage. Kunstenaars reisden veel in die tijd op zoek naar werk. Op die manier werden veel ideeën over de vormgeving van miniaturen verspreid.

- Er bestonden zogenaamde artistieke regio’s. In zo’n gebied dat niet noodzakelijk samenviel met een geografische regio, paste men een specifieke stijl toe bij het vormgeven van de miniaturen.

- Welke rol speelden draagbare voorwerpen in de verspreiding van artistieke ideeën?

- Manuscripten waren echter zelf al ‘overdragers’ van modellen. Ze werden veelvuldig uitgeleend om te kopiëren.

- Soms waren afbeeldingen in manuscripten ook beïnvloed door andere kunstvormen zoals de fresco’s in de Ashburnham Pentateuch (600). De fresco’s uit de kerk van St. Julien in Tours waren hiervoor de ‘modellen’.

Sources for researching model books are relatively scarce. To form a complete picture, input through other ‘channels’ is also needed. It is therefore important to include already existing knowledge on the transmission of ideas in the artistic field in the Middle Ages such as:

The role of the itinerant artist with a collection of models in his luggage. Artists travelled a lot in those days in search of work. In this way, many ideas about miniature design were spread.

So-called artistic regions existed. In such a region, which did not necessarily coincide with a geographical region, people applied a specific style to the design of miniatures.

What role did portable objects play in the spread of artistic ideas?

However, manuscripts were themselves ‘carriers’ of models. They were frequently lent for copying.

Sometimes images in manuscripts were also influenced by other art forms, such as the frescoes in the Ashburnham Pentateuch (600). The frescoes from the church of St Julien in Tours were the ‘models’ for this.

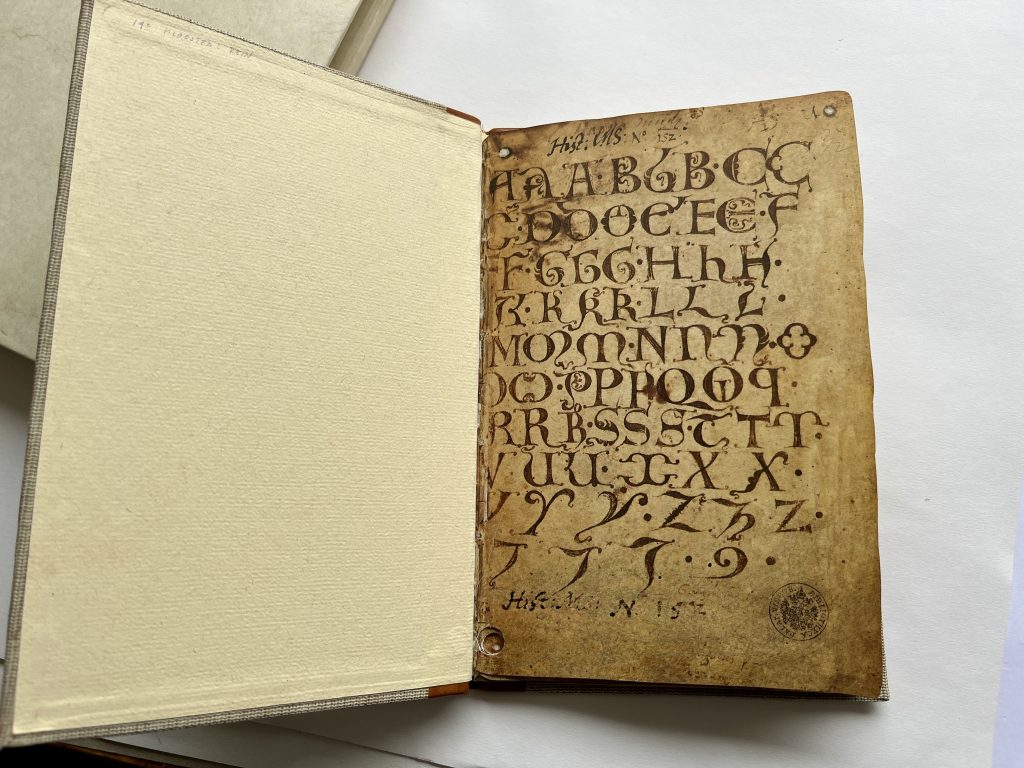

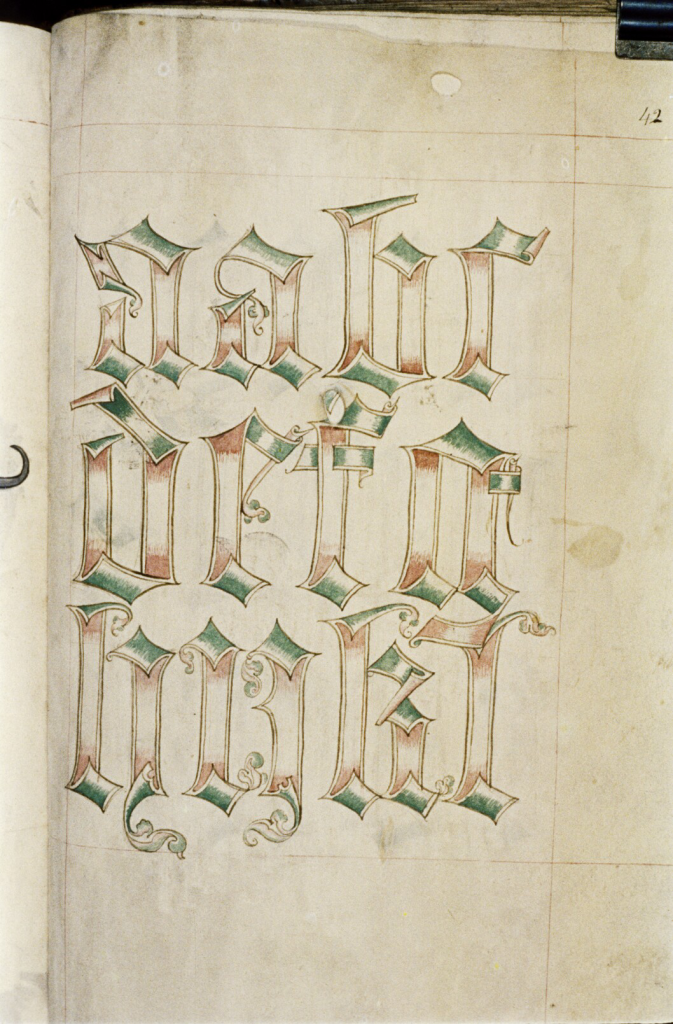

Kenmerken

De onderwerpen die het meest voorkwamen zijn: de mensfiguur en dieren, beide in verschillende stijlen en composities. Bij de afbeeldingen van mensen ging het uiteraard veel over Bijbelse figuren en de dieren hadden veel van doen met de bestiaria die in omloop waren. Hoe verder we in de Middeleeuwen komen hoe meer het naturalisme toeneemt en de techniek gevarieerder wordt. Van invloed was ook dat er meer vraag naar boeken ontstond in de loop van de tijd en dat het hierdoor nodig was om het productieproces van het manuscript te stroomlijnen. Hierbij pasten bijvoorbeeld de techniek van het ‘model pouncing’. Dit werkte als volgt:op de contouren van het model werden kleine gaatjes geprikt en met wat pigment erdoorheen te verstuiven kon men dan eenvoudig het patroon overbrengen. Ook maakte men heel dun perkament of smeerde perkament in met lijnolie, op die manier maakte men dan calqueerpapier. (carta lucida).

Features

The most common subjects were human figures and animals, both in different styles and compositions. The depictions of people obviously involved a lot of Biblical figures, and the animals had a lot to do with the bestiaria in common circulation. The further we get into the Middle Ages, the more naturalism increased and the technique became more varied. Of influence was also that there was more demand for books as time went on and this made it necessary to streamline the manuscript production process. This included, for example, the technique of ‘model pouncing’. This worked as follows: small holes were pricked on the contours of the model and, by spraying some pigment through them, one could then easily transfer the pattern. People also made very thin parchment or smeared parchment with linseed oil, thus making tracing paper (carta lucida).

Over het maken en bewaren van tekeningen

Tekeningen op perkament en papier werden los, gebonden of in een gevouwen vel bewaard. Soms bleef dat zo en andere keren werden ze gebonden. Dat kon als losse katern gebeuren maar ook als onderdeel van een ander manuscript. De bladen met tekeningen waren veelal helder van opzet en met duidelijke lijnen en contouren. Schaduwen werden aangebracht met verdunde inkt en penseel. De compositie was duidelijk en zonder overlappingen want alles moest goed gezien kunnen worden, het voorbeeld moest helder zijn. Verder lijken de tekeningen wat onderwerp betreft in de modelboeken bijeengeraapt, er is geen thematische eenduidigheid. In één boek vinden we afbeeldingen van mensen, dieren, ornamenten etc.

Tegenwoordig krijgen modelboeken voor de middeleeuwse verluchters steeds meer belangstelling. Dit heeft onder andere te maken met de veranderende doelstelling van het kunsthistorisch onderzoek. Het onderzoek naar het werkproces wordt steeds belangrijker. Bij artistieke reconstructies wordt dan ook de vraag gesteld naar de rol van het modelboek.

On making and preserving drawings

Drawings on parchment and paper were kept loose, bound or in a folded sheet. Sometimes they remained that way and other times they were bound. This could be done as separate sections or as part of another manuscript. The sheets of drawings were mostly clear in outline and with clear lines and contours. Shadows were applied with diluted ink and brush. The composition was clear and without overlaps because everything had to be easy to see, the example had to be clear. Furthermore, in terms of subject matter, the drawings in the model books seem cobbled together; there is no thematic uniformity. In one book we find images of people, animals, ornaments, etc.

Nowadays, model books for medieval illuminators are gaining more and more interest. This is partly due to the changing objective of art historical research. Research into the working process is becoming increasingly important. Consequently, artistic reconstructions raise the question of the role of the model book.

In de 14e eeuw neemt het gebruik van papier toe en daarmee ook de productie van modelboeken. Echter steeds meer aandacht komt er voor het artistieke aspect van de tekening en worden modellen in de strikte zin minder belangrijk. De verspreiding van de grafische technieken en de boekdrukkunst in het algemeen versterkte dit proces alleen nog maar.

In the 14th century, the use of paper increases and with it the production of model books. However, increasing attention came to the artistic aspect of drawing and models in the strict sense became less important. The spread of graphic techniques and printing in general only reinforced this process.

Als de Renais

Het boek Exemplum heeft een uitgebreide catalogus met voorbeelden van modelboeken van de vroege tot late Middeleeuwen. Wie wat googelt kan de meeste voorbeelden uit de catalogus wel vinden. Kortom een boek voor wetenschappers maar voor ons als liefhebbers van manuscripten ook heel interessant. Het boek is voor zover ik weet alleen nog tweedehands verkrijgbaar.

The book Exemplum has an extensive catalogue of examples of model books from the early to late Middle Ages. Those who google a bit can find most examples from the catalogue. In short, a book for scholars but also very interesting for us manuscript lovers. As far as I know, the book is only still available second-hand.