Did medieval illuminators use examples?

EXEMPLUM

Model-Book Drawings and the Practice of Artistic Transmission in the Middle Ages

“During the Middle Ages, artistic ideas were transmitted from one region to another and passed on from one generation to the next, in the form of drawings. This kind of handmade reproduction, ‘exemplum’ in Latin, was used to record the form and content of works of art. Some of those drawings have survived in ‘model books’. The author presents a fascinating account of many and various aspects of these drawings with special emphasis on how they contribute to our understanding of the genesis of medieval works of art. Exemplum will be a standard work of reference for many years to come”.

(Ca. 900-ca. 1450). Robert W. Scheller

A while ago, I bought a book with the above title. The reason was that I wanted to learn more about the use of ‘examples’ when making miniatures in manuscripts. What about that actually, were medieval illuminators using examples or also called exempla when making their miniatures? And if so, what role did they actually play in the creation of those miniatures? Did the illuminator do everything by head or did he use models? Were there sketchbooks in the sense we know them? In short, a lot of questions you can ask about the making of miniatures in medieval manuscripts.

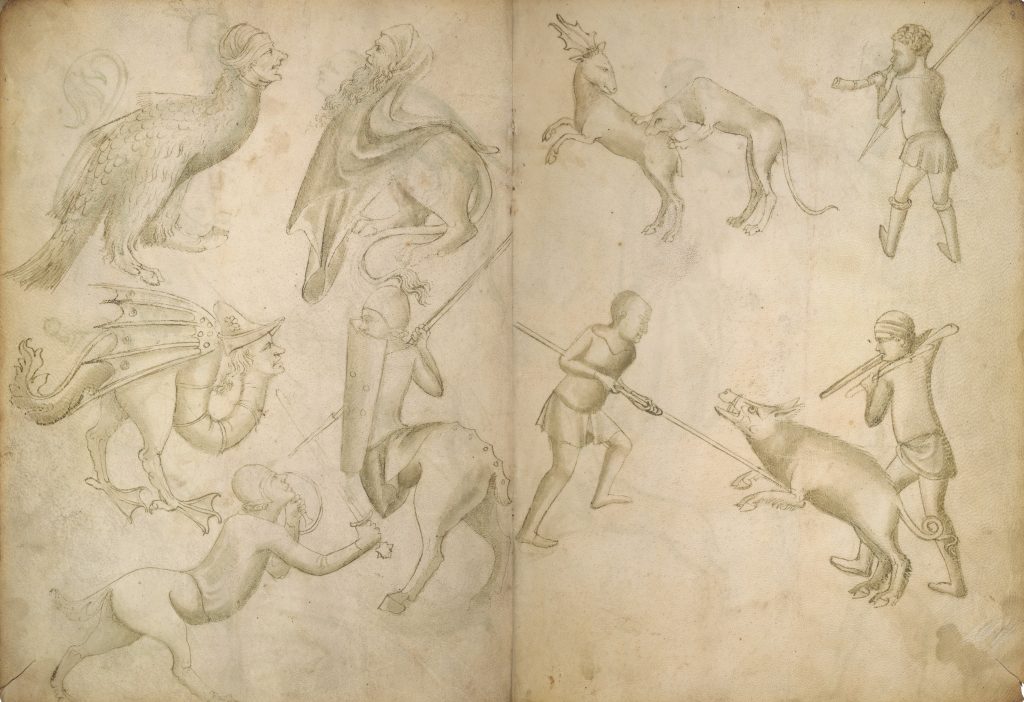

My interest in this has already been triggered in the past by the sketchbook of: Villard de Honnecourt from the early 13th century. I once downloaded it through Gallica, a wonderful sketchbook full of beautiful drawings, with lots of details and very surprising. When looking at his work, you then wonder, why did he create it and how and possibly who used it besides himself? However, when I saw another work: -a facsimile edition of the: Reiner Musterbuch- I was sold and wanted to know more about these kinds of works and their uses. So the book: Exemplum that I came across in the literature on the subject was an excellent guide to study it further.

The book is a very solid scientific study on the matter, so while reading it, I took plenty of notes. Those notes have become the thread of this post.

So this post is not a summary of the book in the strict sense, but a record of personally made notes. Obviously greatly abridged but I still hope it is interesting enough for the reader.

Today, the appreciation of a drawing as we know it is very different from what it used to be in the Middle Ages. Today, we appreciate a drawing as an artistic expression of an artist. The more famous such an artist is, the more appreciation there is for his drawings. Actually, that appreciation of a drawing as an artistic work has only been there since the Renaissance, mid-15th century. It is therefore comprehensible that more drawings have survived from that time onwards than before. Only then was the drawing worth preserving in its own right as a ‘work of art’.

Is this the reason that more drawings have survived from the Renaissance than from the Middle Ages? Or are there other factors that also played a role? In the book, the author continues to search for answers.

Bron: Pierpont Morgan Library

Some guiding principles in researching model books and their use

As mentioned above, drawing in the Renaissance was an artistic expression of an artist himself. The creative power of his personality or individual was made directly and clearly visible. This is precisely why the drawing was increasingly appreciated from that time onwards.

In the Middle Ages, however, the drawing was a preparatory phase, a study of nature, a composition sketch, a working drawing. While working, the draughtsman had a very diverse or just specific purpose in mind.

Drawings made with a lead pen, brush were part of the steps to be made to achieve a goal. They were an essential part of that. You could say they had more of a practical use.

Drawing was also very important in the training of the artist. We can read that from Cennino Cennini in his: ‘Handbook of the Artist’.

Still unanswered is the question of why then so little remains of all those drawings from the Middle Ages.

Some of the reasons listed

Drawings, as already mentioned, had no artistic value and were therefore not kept with care. They served a very specific purpose and upon achieving it, the drawing was not worth much anymore. When the job was finished, the drawing could be discarded

What is hard for us to imagine is that the material to draw on was very scarce and expensive. We have a lot of choices for choosing a support for making a drawing. But before the 15th century and the introduction of paper, only parchment was available as a durable medium to draw on.

Other and less durable supports were also used to make drawings on. Widely used was the sink. These were used by merchants for recording transactions, among other things, but also for practising writing and making drawings. However, here too, almost everything has been lost.

Bron: Pierpont Morgan Library.

Research on model books and their role in transmission of knowledge.

The research on model books has long used Julius von Schlosser’s thesis: Künstliche Überlieferung. The idea behind this is that the artist was guided not so much by nature but by models which were rooted in Antiquity.

From Antiquity onwards, certain models would have developed that were more leading in the design of miniatures than nature itself. In other words, the artist looked more at the model in front of him or formed in his mind than at the form in nature around him. Now they we are used to drawing after nature but for a medievalist it was different.

The model also called exemplum is one side, the starting point on the way to the final product, that is where the artist started. To make his way to the final product, he made drawings. We would say designs. In this view, the drawing was the bridge between the exemplum or example and the final product. This has long been a key idea in all research on the role of model books

In more recent research, however, this view is subject to criticism and more nuanced thinking. In the book exemplum, Scheller examines on this. However, this post is not a real study and I have only included the most relevant comments in this post.

According to Scheller, a detailed semantic study is also needed for the proper understanding of art vocabulary in the Middle Ages when researching model books. It is still not so easy to make sense of the terms used in the sources used for research.

Words used in sources like: imitare, praesentare, exemplum, exemplar, forma, similitudo, imago need to be seen in a broad context, and why really?

BM, lat. 4

Language is a wonderful thing, it is one of the wonderful gifts given to human beings. But language can also be tricky, it pays close attention to what and how you say it and what words you use. You can use words to praise another person but also to humiliate them. Those who live consciously deal with language consciously.

If this is of importance in everyday life, then certainly also in researching sources that talk about models and their use in miniatures. Without going into too much detail, we should realise that the above words were used, shaped and interpreted by medieval people.

In doing so, they used the philosophy of Plato, Aristotle and certainly also the theology of the Church Fathers, which makes it all rather complex, too much for this post. The book, however, obviously delves deeper into it and it is quite fascinating.

Sources for researching model books are relatively scarce. To form a complete picture, input through other ‘channels’ is also needed. It is therefore important to include already existing knowledge on the transmission of ideas in the artistic field in the Middle Ages such as:

The role of the itinerant artist with a collection of models in his luggage. Artists travelled a lot in those days in search of work. In this way, many ideas about miniature design were spread.

So-called artistic regions existed. In such a region, which did not necessarily coincide with a geographical region, people applied a specific style to the design of miniatures.

What role did portable objects play in the spread of artistic ideas?

However, manuscripts were themselves ‘carriers’ of models. They were frequently lent for copying.

Sometimes images in manuscripts were also influenced by other art forms, such as the frescoes in the Ashburnham Pentateuch (600). The frescoes from the church of St Julien in Tours were the ‘models’ for this.

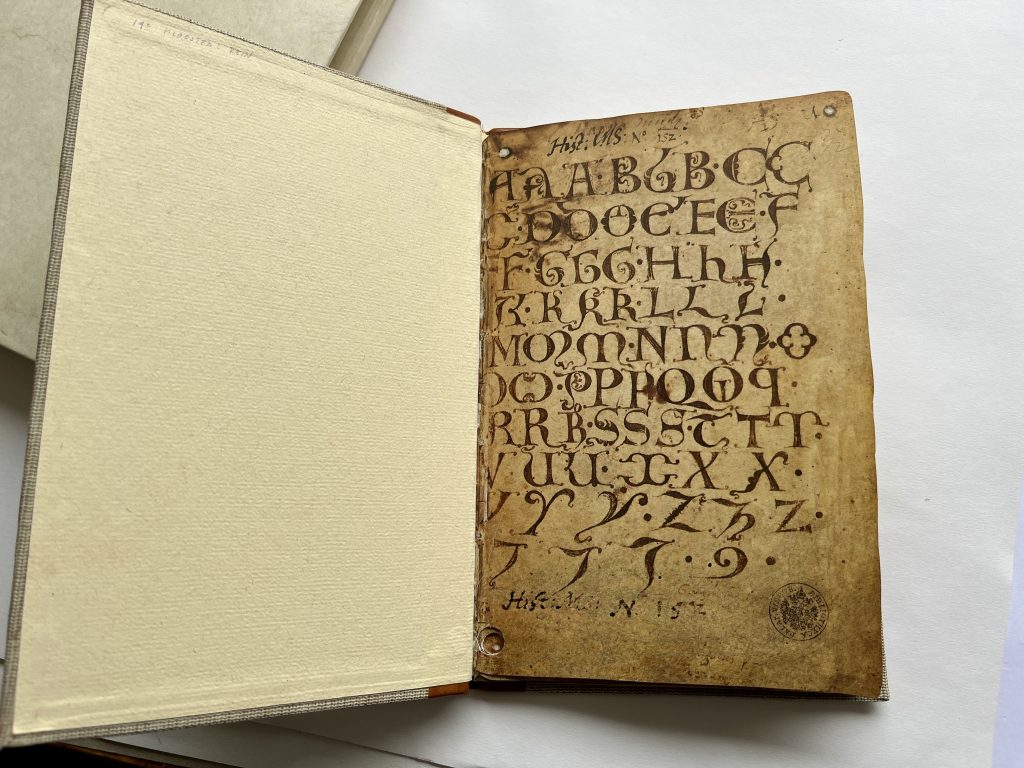

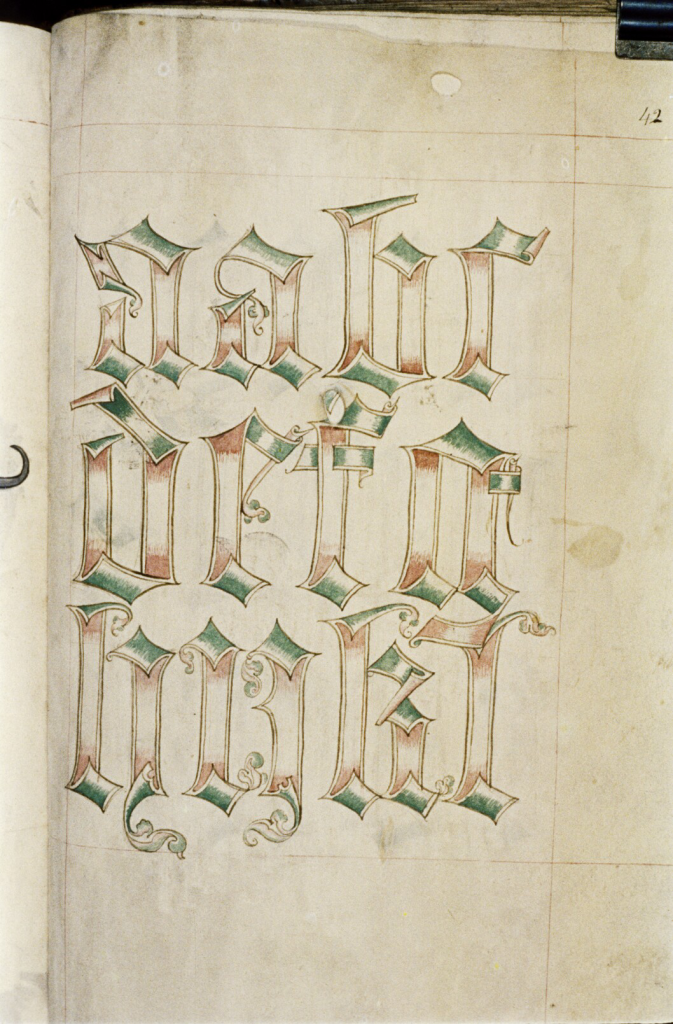

Features

The most common subjects were human figures and animals, both in different styles and compositions. The depictions of people obviously involved a lot of Biblical figures, and the animals had a lot to do with the bestiaria in common circulation. The further we get into the Middle Ages, the more naturalism increased and the technique became more varied. Of influence was also that there was more demand for books as time went on and this made it necessary to streamline the manuscript production process. This included, for example, the technique of ‘model pouncing’. This worked as follows: small holes were pricked on the contours of the model and, by spraying some pigment through them, one could then easily transfer the pattern. People also made very thin parchment or smeared parchment with linseed oil, thus making tracing paper (carta lucida).

On making and preserving drawings

Drawings on parchment and paper were kept loose, bound or in a folded sheet. Sometimes they remained that way and other times they were bound. This could be done as separate sections or as part of another manuscript. The sheets of drawings were mostly clear in outline and with clear lines and contours. Shadows were applied with diluted ink and brush. The composition was clear and without overlaps because everything had to be easy to see, the example had to be clear. Furthermore, in terms of subject matter, the drawings in the model books seem cobbled together; there is no thematic uniformity. In one book we find images of people, animals, ornaments, etc.

Nowadays, model books for medieval illuminators are gaining more and more interest. This is partly due to the changing objective of art historical research. Research into the working process is becoming increasingly important. Consequently, artistic reconstructions raise the question of the role of the model book.

In the 14th century, the use of paper increases and with it the production of model books. However, increasing attention came to the artistic aspect of drawing and models in the strict sense became less important. The spread of graphic techniques and printing in general only reinforced this process.

The book Exemplum has an extensive catalogue of examples of model books from the early to late Middle Ages. Those who google a bit can find most examples from the catalogue. In short, a book for scholars but also very interesting for us manuscript lovers. As far as I know, the book is only still available second-hand.

King with courtier: Braunschweiger Skizzenbuch