Beauty in shades of grey

Those who think of medieval miniatures mainly see colourful depictions provided with the necessary golden illuminated details. Yet there was a period when, besides colour miniatures, people consciously gave up colour and limited themselves to black and white and various shades of grey. Years ago, I first came across these ‘grey’ miniatures at the Royal Library in Brussels. And recently on a visit to the KBR’s museum, they caught my eye again with the look so characteristic of them. They are beautiful with very subtle representations, designed with a wide range of shades of grey.

The generic term: grisaille comes from the French: gris = grey. On the one hand, it refers to a technique in which the painted representation is constructed in black and white and shades of grey. On the other hand, the word also means a genre because a grisaille occurs on panel, in glass painting and as a miniature in manuscripts.

The French codicologist Denis Muzerelle writes in his famous ‘vocabulaire codicologique : “Grisaille = camaïeu using various shades of grey and white and black”. Camaïeu, in turn, denotes a monochrome painting technique in one colour.

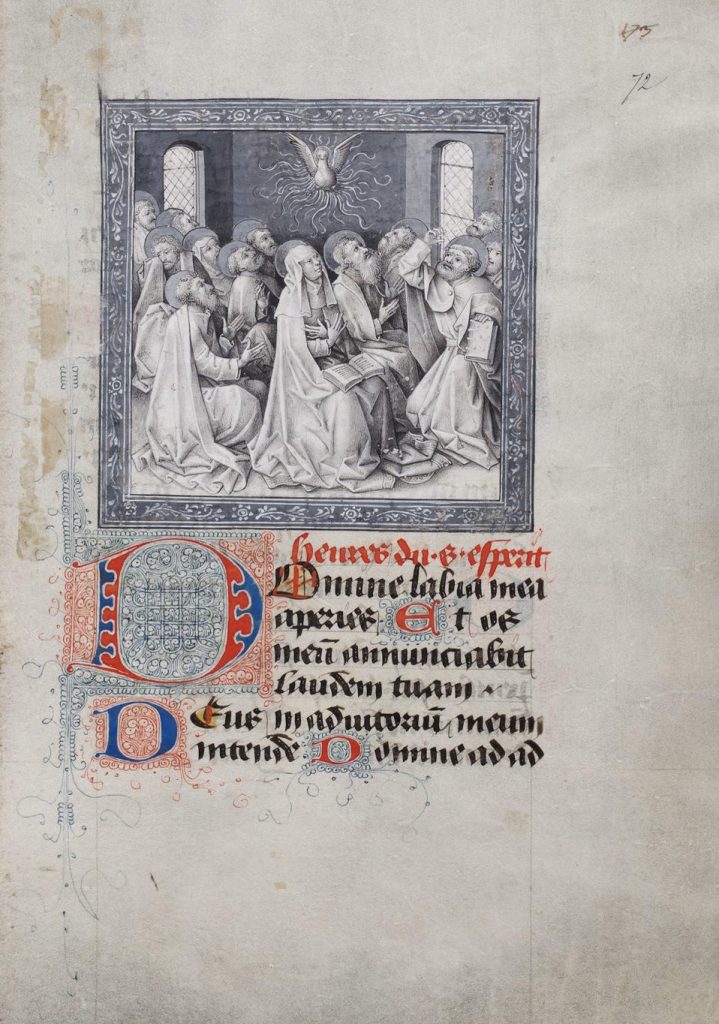

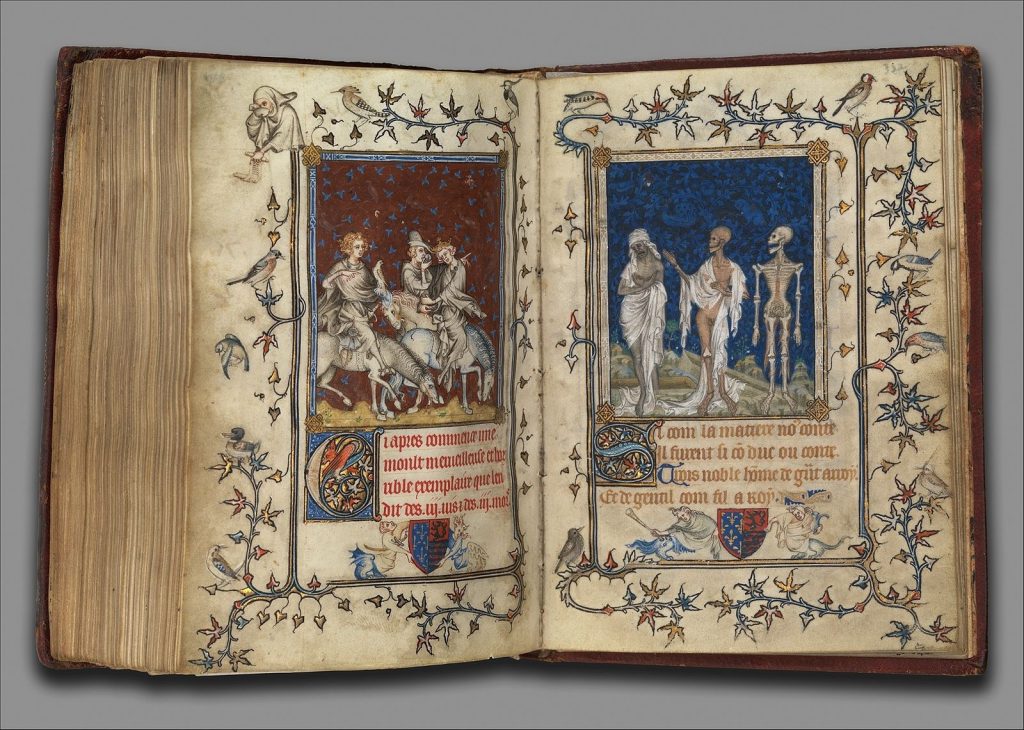

Historically, the term grisaille is more recent than the technique. The word: ‘grisaille’ was only documented in its current meaning in its final heyday in the 17th century. Sources from the time when grisailles were made spoke of: ‘Images de noir et le blanc’. As a legacy of Antique sources, it was also referred to as: ‘color lapidum’ or ‘stone colour’. It is also important to know that people did not always stick strictly to black, white and grey in the painted miniature. We sometimes see that people used brown, blue and flesh colour in addition to shades of grey. Sometimes only the figures in the composition were painted in grisaille and the background was given colour. In such cases, one speaks of semi-grisailles.

In this post, I want to focus mainly on grisaille as miniatures in manuscripts. I will leave panel painting and glass painting alone. However, it is good to pay some attention to the historical context of grisaille miniatures. I also want to share my own experiences and show you how to make them yourself. The latter is a real revelation if you have worked a lot with colour.

Oudenaarde, c. 1450-1460

Some context

The use of grisaille possibly originated in the 12th century after an attempt by the Cistercian order to ban the use of colour in stained-glass paintings. In the 12th and 13th centuries, grisaille windows became increasingly popular and were placed alongside figure portraits of coloured glass in medieval churches. Italian artist Giotto (c. 1267-1337) is credited for the first use of grisaille in murals in the early 14th-century allegorical fresco of the Seven Virtues and Vices. On the north and south walls of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, the monochrome figures of the Virtues and Vices are painted to resemble stone and marble sculpture.

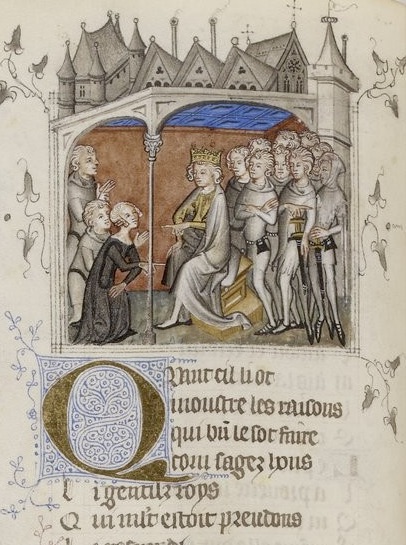

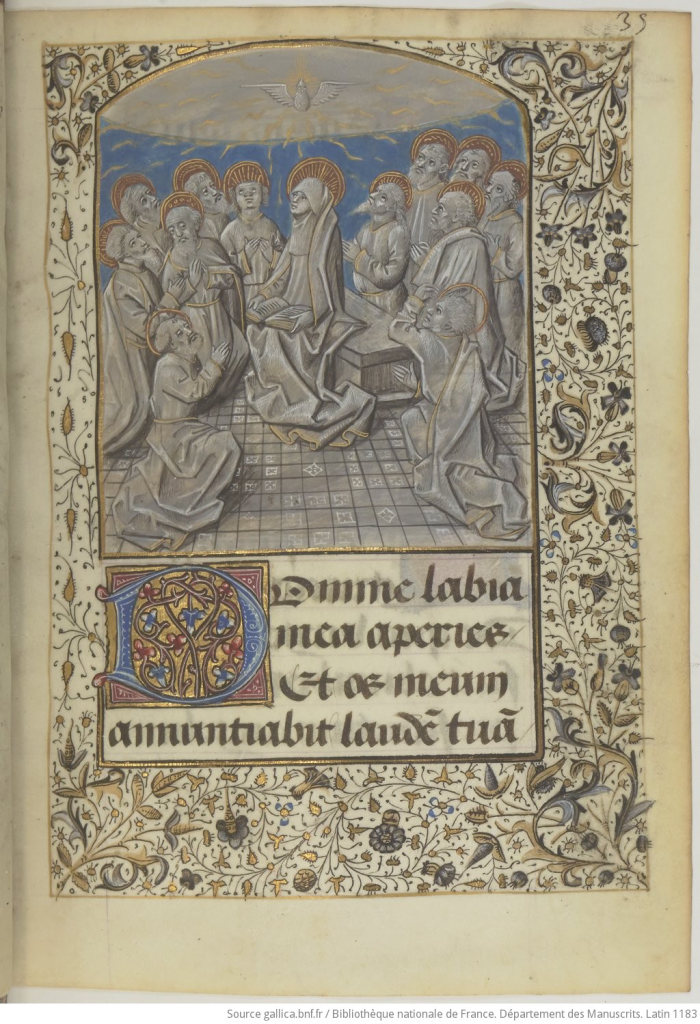

The first grisailles accompanying miniatures in manuscripts appear in France around 1325 with the work of Jean Pucelle. He worked in Paris, among other places, and illuminated a book of hours for Jeanne d’Évreux (1324-1328) in which he applied the technique of grisaille to a very small format (9.4 x 6.4 cm)! He must have been a very skilled illuminator to execute this work in such a format. (See image below).

Photo: wikipedia.

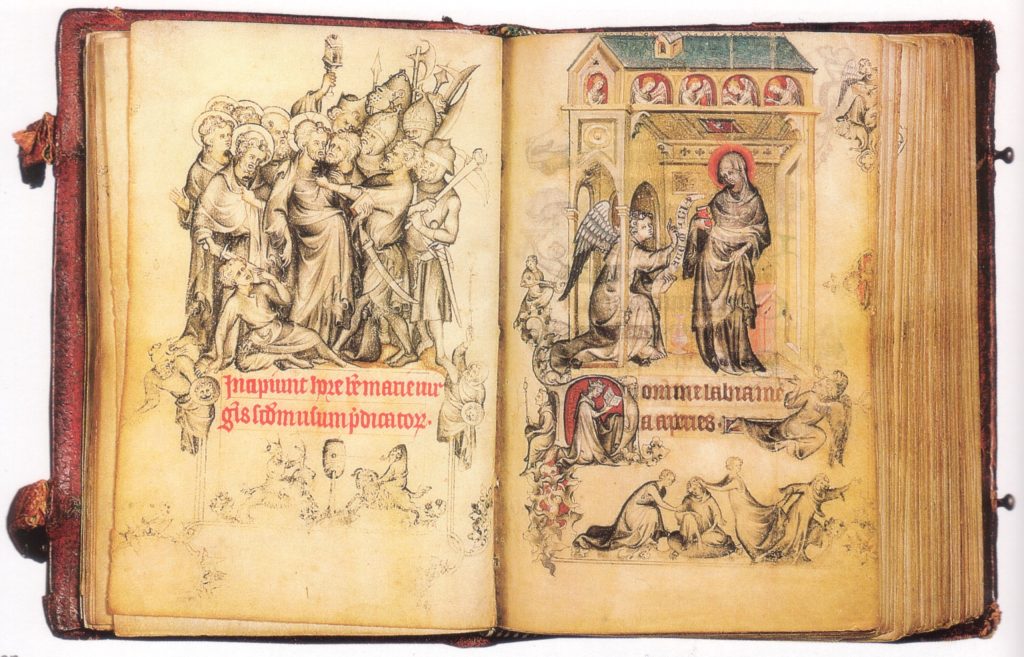

The work was commissioned by Charles IV of France for his third wife Jeanne d’Évreux. We are talking about a semi-grisaille here because he used red, blue and green as well as a flesh colour in addition to the shades of grey. Jean Pucelle inspired a whole number of 14th-century Parisian illuminators including Jean le Noir. Among others, he illuminated the Psalter of Bonne of Luxembourg (1348-1349), an image of which is below.

In the period between 1350 and 1380, grisaille became fashionable in Paris for miniatures in luxury manuscripts. They then disappeared to reappear in the Burgundian Netherlands around 1425, where van Eyck and the master of Flémalle in particular started using the technique on panel. They made paintings of figures on the back of retables (altarpieces) with a strong trompe-l’oeil effect. These were images that suggested they were made of stone (statue).

John the Baptist and John the Evangelist on the back of the “Lam Gods” by Hubert and Jan van Eyck

At the Burgundian court, grisaille became important among the illuminators working there from 1460 onwards. It is referred to in literature as a ‘court style’. Remarkably, the grisailles for the Burgundian court are less linear than those from France and have more of a painterly quality.

About the technique of grisaille

There has been a focus on grisailles in manuscripts for several decades. In 1986, a special exhibition was devoted to them at the then Albert Ie library, now the Royal Library in Brussels (KBR). A modest catalogue, ‘Miniatures en Grisaille’ was published by Pierre Cockshaw. Yet no thorough laboratory study of the materials and working methods used was yet undertaken.

In recent years, though, that has changed. On my search for relevant literature, I came across an article by Lieve Watteeuw and Marina Van Bos: ‘Black as Ink. Materials and Techniques in Fifteenth-Century Flemisch Grisaille Illuminations by Jan de Tavernier, Willem Vrelant and Dreux Jehan’. The article is in the wonderful book: New Perspectives On Flemisch Illumination published by Peeters in Leuven in 2018.

The research conducted by the authors revealed that among grisaille painters, the palette was broader than white, black and shades of grey. Various other colours were mixed with the grey tones, creating very subtle colour nuances. According to the writers, the grisaille palette was almost as varied as the palette of illuminators who worked in colour.

In various colour washes, they added vermillion, minium and other organic shades. They also used carbon ink, gallnut ink or a mixture of both, which were further supplemented with white lead. They also used shell gold for highlights and azurite for air. In the sky, silver was used for the clouds, as in the case of Willem Vrelant.

The appreciation of the colour grey increased in the 15th century and became almost as high as the colour black. This tendency was visible in princely dress, panel painting and in book painting, among others.

Furthermore, grisaille was a cheap form of decoration where raw materials and preparation were not expensive. However, it did demand a lot from the artistic capacity of the illuminator to apply this technique.

The grisailles from the aforementioned materiality study were all made between 1458 and 1480. They come geographically from the area in which the cities of Bruges, Ghent, Brussels, Lille and Valenciennes are located. All these cities were under Burgundian rule at the time.

Getting started painting a grisaille yourself

There are actually two groups of grisailles in manuscripts. The result of both is a painting in grey tones but the painting process is different.

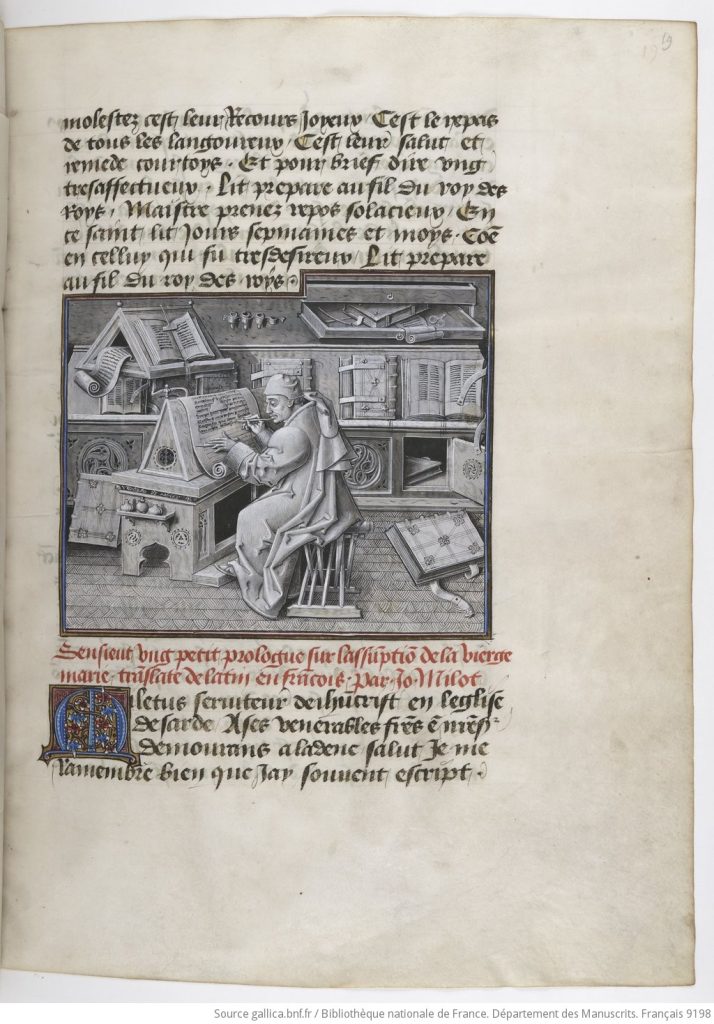

- The first method of painting starts from a light background and makes the shadows progressively darker. The work of the illuminator Andre Beauneveux is a fine example of this. See image.

- The second way first darkens the ground and then works progressively lighter with one or more layers of white. Jan Tavernier worked this way. See image.

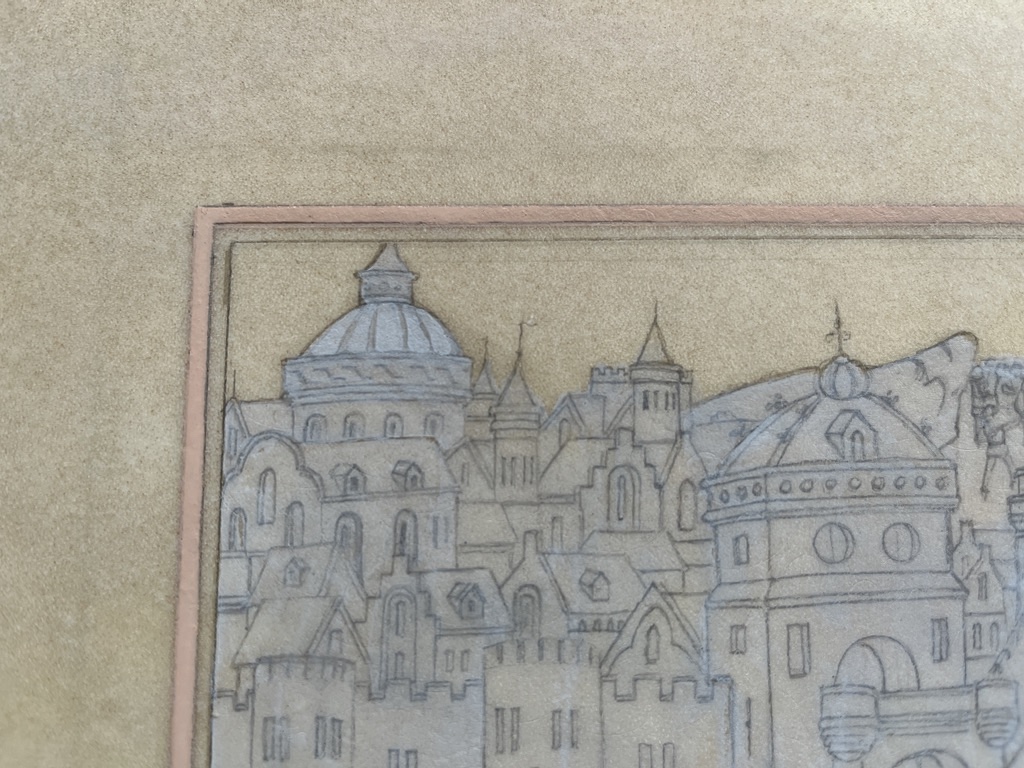

Step by step to work on your own grisaille

We stretch a piece of parchment. For this exercise, I used calf parchment with a somewhat ‘antique’ look of a red-furred calf. First we apply the drawing and frame the representation well. Then I applied a first, very transparent light grey layer as evenly as possible with a flat brush. Trying to do it watery and make as few streaks as possible. Would have preferred a slightly darker layer but hesitated because of the very dark colour of the parchment. So I opted for a mid-grey as a base.

We apply the gesso to the border and then the gold leaf.

We now paint the frames with red and black.

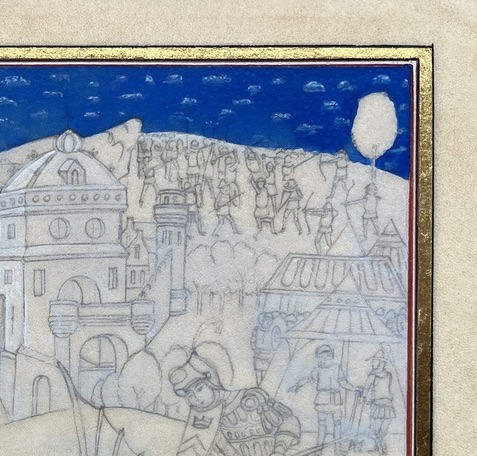

In this case, we first apply the sky with the clouds. Have chosen light, white clouds here. In the original, the clouds the painter used silver. Those clouds have now turned black due to oxidation.

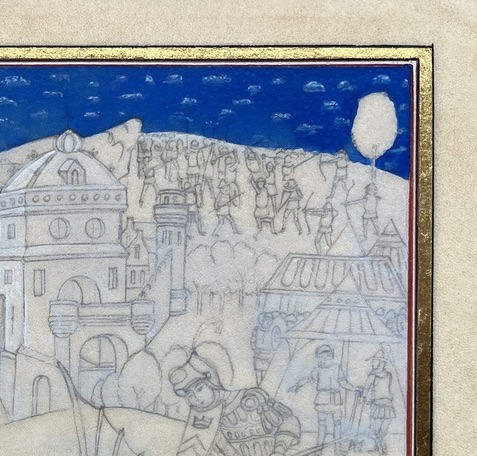

Now continue bit by bit. Pay close attention that the contrasts between black and white in the background are weaker than in the foreground. I applied the dark tones first and then the highlights with white. See the image below for this.

Finally, the detailed foreground with the strongest light and dark contrasts on it. Furthermore, shell gold has been applied to small details. This is not easy to see on the screen.

It’s done, my first grisaille. Quite an experience after all those miniatures with all the colours. To learn a bit I started by making a copy of:

Fight of consul Marcus Actilius with the mythical animal. Leonardo Bruni, De primo bello punico [French version]. Willem Vrelant, Bruges, before 1467.Brussels, KBR, ms. 10777, f. 58r.

Literature:

New perspectives on Flemish illuminations: L.Watteeuw 2018.

Le livre d’heures de Jean Gros. Art de l’enluminure nr 54.

Colour Lapidum: A survey of late medieval grisailles. Till-Holger Borchert.

Philip the Good’s grisaille book of hours and the origins of a new court style: Sophia Rochmes.